Who Was Osamequin?

-

“I guess I should officially welcome you to the ancestral homeland of the Pokanoket tribe and, you know, our ancestral homeland was comprised of Seekonk, Swansea, Rehoboth, Barrington, Bristol, Warren, and East Providence. My name is Tracy Dancing Star Po Pummukoank Anogqs. I am Sachem of the Pokanoket tribe of the Pokanoket Nation. ” (Tracey) Together, these lands are known as Sowams to their First People. The Pokanoket people have lived in Sowams for over 10,000 years in close relationship with its land and waters. “The tribe, we moved, we hunted, we lived within this land.” (Tracey)

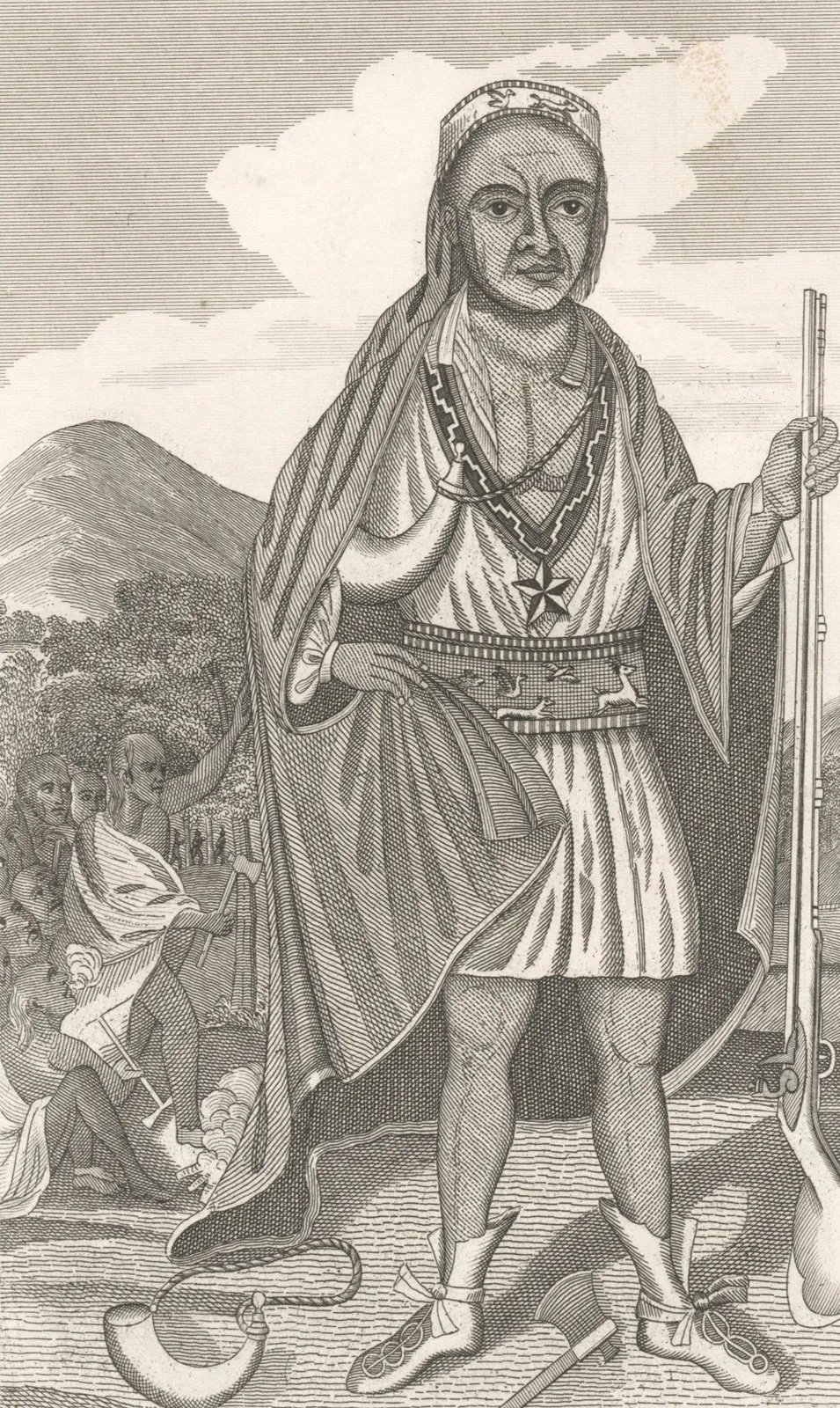

The name of this farm today comes from the Pokanoket leader Osamequin. Who was Osamequin? “He was the Massasoit at the time when the Pilgrims came here, and Osamequin is his name, Massasoit is a title, it means great leader. And a lot of people think that Massasoit is his name, but it's Osamequin, which is Yellow Feather in our language. My name is Po Wauipi Neimpaug, which is Winds of Thunder in our language. And I am here Sagamore of the Pokanoket tribe of the Pokanoket nation. I’m the ninth generation great grandson of the Massasoit Osamequin.” (Bill)

“Osamequin, his tribe was the Pokanoket tribe.” (Tracey) The Pokanoket tribe was the headship tribe of a loose confederation sprawling throughout the land known as New England. The Massasoit Osamequin’s home here in Sowams was the political seat of more than 60 tribes, bands, and clans that held tribute and gave allegiance.

“So what is important about Osamequin is that he is the one who signed the 1621 peace treaty with the Pilgrims.” (Tracey) Many of us have learned to think of the Pilgrims’ arrival at Plymouth Rock as a watershed moment of first encounter between Europeans and Indigenous peoples. But this isn’t true. When the English arrived at the Wampanoag village of Patuxet, the village’s Native people had already experienced the devastating effects of contact with Europeans. “When the Pilgrims came here in 1620, actually, that was right after the Great Dying.” (Bill)

From 1616 to 1619, diseases carried by European fishermen, traders, and enslavers swept down the Atlantic coast, devastating Native communities from Maine to Massachusetts. This period is remembered by Native people throughout the Northeast as the “Great Dying.”

Before the Great Dying, Patuxet was a thriving Wampanoag village home to as many as 2,000 people. But in November of 1620, the Pilgrims encountered a village emptied by deadly disease and European enslavers who had captured Patuxet people and sold them into slavery. As winter set in, the Pilgrims survived by scavenging Indigenous graves and food stores of abandoned homes.

It was in this context of profound loss and disruption that the Massasoit Osamequin, from his home here in Sowams and in council with other Indigenous leaders, decided to enter into a treaty with the English in 1621. “We went from a tribe of over 3000 warriors to under 300 warriors, and yet the Massasoit was the used diplomacy to take and maintain his reign over all the sides. So basically, he must have been quite a diplomat.” (Bill) “And, you know, that peace treaty lasted for, what, 54 years.” (Tracey)

In those years, the Pokanoket and other Indigenous peoples shared their knowledge with the struggling European settlers, helping them acclimate to the landscape. “We knew what to eat, what to farm, what to hunt, when to hunt, and these were all things that had we not taught, you know, the colonists when they came over, they wouldn't have survived, they wouldn't have survived. So they they you know, learned from us how to survive.” (Tracey)

Osamequin’s son Metacom, who also adopted the name King Philip, inherited the headship of the Pokanoket nation in 1662. But peace became hard to maintain as growing populations of settlers continued to encroach on Indigenous lands. “They were pushing us, you know, pushing us out. They were limiting the ways of our life and how we've always He's, you know, survived. And the tables all have suddenly turned, you know, we had helped them so much. And the tables just turned and they were hindering and harming us. And so King Philip did what any leader, any loving good leader of any people would do. He put his foot down and said, No, this is this isn't okay. And he had to fight for the survival in the way of life of our people. And unfortunately, we know how the war ended.” (Tracey)

It’s not entirely clear who named this place Osamequin Farm, or when—it’s definitely been decades. But the name Osamequin reminds us of the histories of colonization that have shaped this land—and the ongoing connections of Pokanoket people today to their ancestral lands and waters.

“I just want to say that, you know, our people, you know, inhabited these lands for, you know, more than 10,000 years prior than, you know, to colonization, and the creator put our people here to be stewards of this land to care for this land, and to care for everything on it. And I just want to just, you know, honor my ancestors who did just that they took care of this land, and they took care of everything on it. They lived in peace, balance and harmony, you know, on this land, and I just want to pay respect for the Pokanoket people today who are still, you know, stewards of this land, taking care of this land and trying to restore balance to it.” (Tracey) “The Pokanoket people are alive and well. We’ve survived, you know, through 400 years. We’re still here.” (Bill)

Through the rest of this introductory tour, we’ll learn more about this landscape’s layered histories, and hear from many people who have loved, cared for, and shaped this place.

-

-

In order of appearance:

Tracey (Dancing Star) Brown - Sachem of the Pokanoket Tribe

Jordan Schmolka - narrator

William (Winds of Thunder) Guy - Sagamore of the Pokanoket Tribe

-

Walk down Walnut Street until you reach the small white bridge (about 250 feet). Listen to the next track from the bridge, looking out over the expanse of the marsh on your left!