In the Field: Flower Hill

-

“This is the field that we call Flower Hill. It's one of our favorite fields on the property, just aesthetically, and it's kind of set off in its own world. So it feels like a special place no matter what time of year, even if things aren't growing.” (Sarah)

“When we were conceiving of Osamequin farm as a farm that would grow crops and thinking about bringing in different farmers into the cooperative, we definitely wanted to keep balance in mind. And so when we had conversations with different farmers who were going to join the collective, we ended up with a bunch of different vegetable farmers and some herb farmers, but we didn't have anyone growing flowers. And so we decided that that would be the thing that we would cultivate, as Osamequin farm.” (Sarah)

So many different flowers grow in this field. “We kind of separate things out by section. So we've got a perennial section where we grow perennials. So that's where the peonies are, and we have some herbs like mint, anise, hyssop, lovage, salvia, hyssop, things that we can use as kind of accent, um, flowers or foliage. We're also growing some foxgloves and columbines and things like that in there, although those are younger. And then we have our annual section where we grow all of our annuals…We've got our Zinnias, we have snap dragons and I don't know all sorts of things.” (Emily Shapiro)

“We love to find all the different ways that there are to share flowers because some people might consider them sort of a luxury item. But we're really trying to grow flowers for the people. So we find all the different ways that we can to get flowers into people's hands, we have them at the farm stand in pre arranged bouquets, we also have our build your own bouquet, set up at the farm stand so people can sort of arrange themselves we do pick your own events in the field. And we also do flowers for events like weddings and birthday parties and anniversaries and things like that. Any way that we can find to really share the joy of being in a field full of flowers and interacting with flowers with as many people as possible. That's our goal.” (Sarah)

“While people obviously need food, and they need fresh food and healthy food, and you know, food grown without chemicals, people often don't think about the value of flowers or the impact of flowers. But the flowers that you buy at the grocery store, even sometimes were often the flowers you can get from a florist had been flown in from abroad or from South America, they're often treated with tremendous amounts of chemicals to keep them looking fresh, and to keep them alive during that travel. And then there's also the labor conditions for the folks that are growing and harvesting those flowers, there's really a lot behind something that seems quite simple. And so we take a lot of pride in providing, you know, fresh, beautiful, fresh smelling clean flowers, but also flowers that don't have that tremendous climate impact and social impact. Our flowers are certified naturally grown, which is a certification that is peer reviewed. We love being certified naturally grown, it really means a lot to us. I always tell people that there’s no way you can fool a farmer. So if we’re being inspected by another farmer, you know that we are holding ourselves to the highest standards.” (Sarah)

Those standards aren’t limited just to flowers. Thanks to the vision and care of Anne Jencks, responsible, organic land care practices have been utilized on the property for decades. “Whatever it is that we're cultivating. We're trying to really grow healthy soil and healthy soil grows healthy crops. And there's a lot of different ways that we do that. One is by not using any chemicals, we're not bringing in any sort of foreign substances that the soil wouldn't naturally have or understand. All of our resident farmers are required to follow organic standards, we don't require that they become certified organic and follow an inspection timeline, but they are required to stay away from products that are not approved for organic use.” (Sarah)

“And then we're doing everything we can to cultivate a healthy environment in the soil for the microorganisms and the bacteria and the fungi that are going to make the minerals that are naturally occurring in the soil available to our plants. And so one of the important ways that we cultivate that environment for the living creatures in the soil is by being a no till farm. Conventional crop farming involves basically running machines through the soil to in one way or another flip over and pulverize the crops that were there previously and turn the soil into a fresh seed bed that's, you know, simple for a piece of equipment to work and it looks sort of fresh and clean. You'll notice that when you drive around in the spring or in the fall, you'll see, you know, a cornfield having just been turned and it looks like just fresh bare ground. But our strategy is to try and leave living roots in the soil for as much of the year as possible, if not all year round. So at the end of the season, rather than run a piece of equipment or hand tools through the soil to sort of get a fresh slate, we might come through with hand pruners or loppers, and chop off plants at the base and leave their roots in the ground because those roots are holding the soil structure together. They're creating habitat for different organisms that live in the soil. And they will break down over time, so there's really no reason for us to pull them out.” (Sarah)

“One of the ways one of the strategies that we use in no till farming, and many of our resident farmers here in the cooperative use the strategy as well, is to kill weeds or to create a stale seed bed by solarizing the soil and they we do that with the use of tarps.” (Sarah) “The tarps are pretty big part of making things work.” (John) “If we know we're not going to use an area of the field or just a bed in the field, for a period of time, we might lay this woven plastic fabric called landscape fabric onto the soil. And that blocks out the light enough to kill the weeds that are underneath. But the woven fabric lets water through. And so we're not starving the microorganisms in the soil. We're just preventing weeds from growing until we're ready to use that bed. And that's a great strategy for sort of keeping on top of a large amount of space in a no till system.” (Sarah)

“What happens over time as the soil develops like a column of nutrient exchange and water exchange, that is, in my mind replicates more how like a forest or like a natural habitat that doesn't get tilled might preserve its nutrients, store carbon and create a suitable soil environment for plants to thrive. I love seeing the productivity and health in the soil that was just an empty field when I first saw it, I think that's like, pretty moving. When I drive down Prospect Street even in the wintertime, I see like, all this evidence of so much food coming out of the land and makes me feel super happy.” (Sophie)

This approach to working with the landscape to encourage natural processes applies beyond our fields at Osamequin Farm. Beth Brandon is a landscape designer with a focus on native plants. She’s landscaped parts of this property, especially around the entrance and driveway. “What I really am trying to do is just give the garden or the landscape, what it might like, what little help it might need to do its own thing. So I love plants that are happy here, spread on their own feed wildlife and pollinators. I just love to walk along the edge of the blueberries and see what's in there and let that inform also what I do. I really like to just see what’s going on here and then try to like encourage more of that.” (Beth)

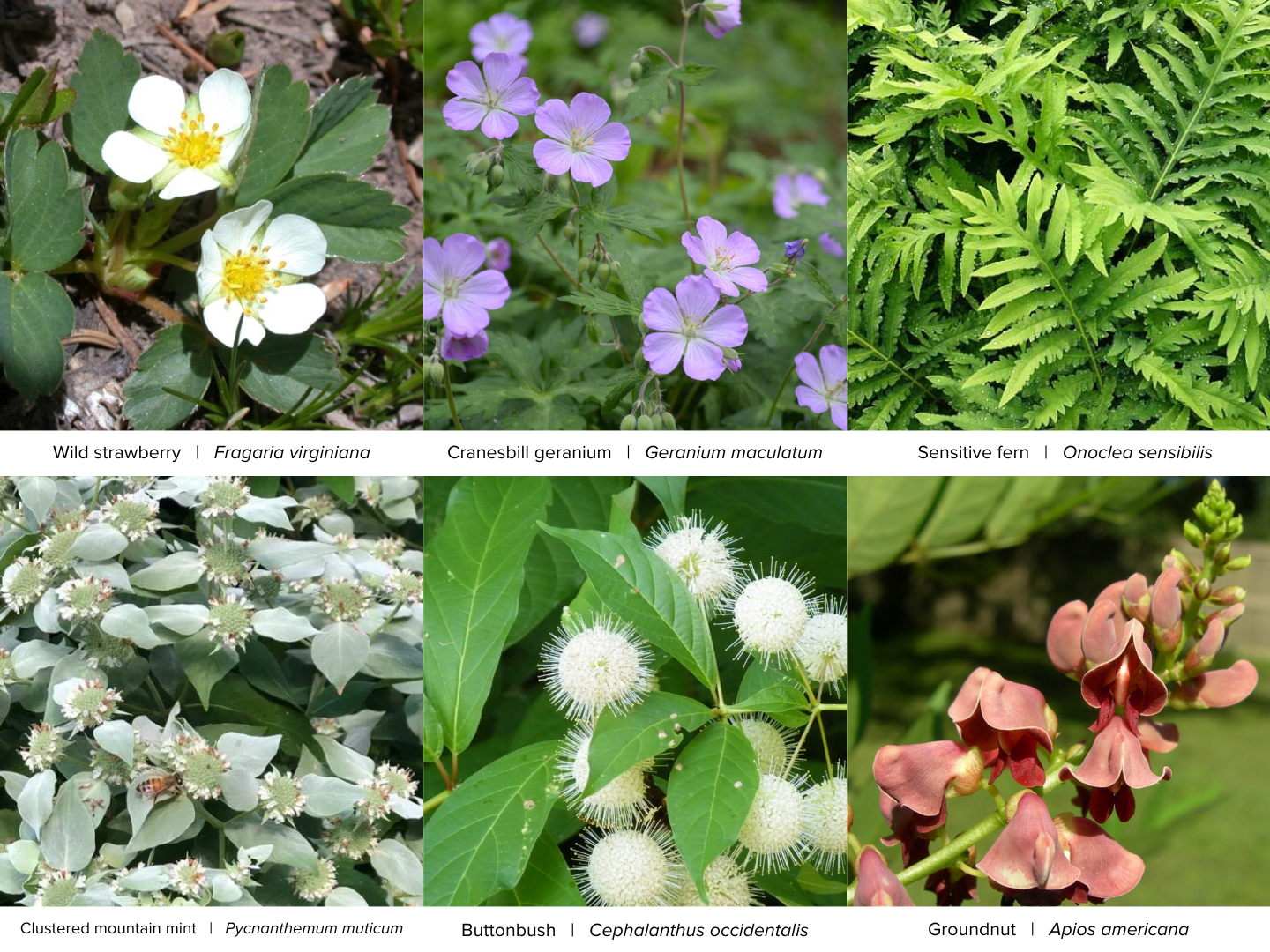

Thanks to Beth’s work, a trip down farm’s the driveway can feel like a treasure hunt of native plant species…wild strawberry, cranesbill geranium, sensitive fern, clustered mountain mint, buttonbush, groundnut…the list goes on. “If I keep growing the plants here and saving the seeds from the plants that are growing here, then over time I will be developing, you know seedbank have from plants that are adapted to this area. I think that we should also put more stock in plants’ ability to adapt themselves. And to keep in mind, all of the ecological implications of that and what they're adapting to, and the animals that rely on them.” (Beth)

Now, make your way over the little bridge at the edge of the field to the pond for a final reflection.

-

-

In order of appearance:

Sarah Newkirk - Farm Director

Jordan Schmolka - narrator

Emily Shapiro - Osamequin Farm resident and flower hill manager, resident farmer (Night Garden)

Sophie Soloway - former resident farmer (Hocus Pocus Farm), current board member

Beth Brandon - ecological horticulturist and landscape designer

-

After walking around the field, cross the small footbridge at the opposite side. When you reach the side of pond, feel free to sit on the big rock at its edge, or on the lichen-covered bench, as you listen to Track 10.