Marsh Stories

-

From here on the little white bridge, look for the water around you… Pooling in the small pond, maybe rippling in the breeze…trickling under the bridge from the expanse of the open marsh on your left. Notice how the marsh looks this time of year…is it blazing with the reds and oranges of fall? Just waking up in springtime green?

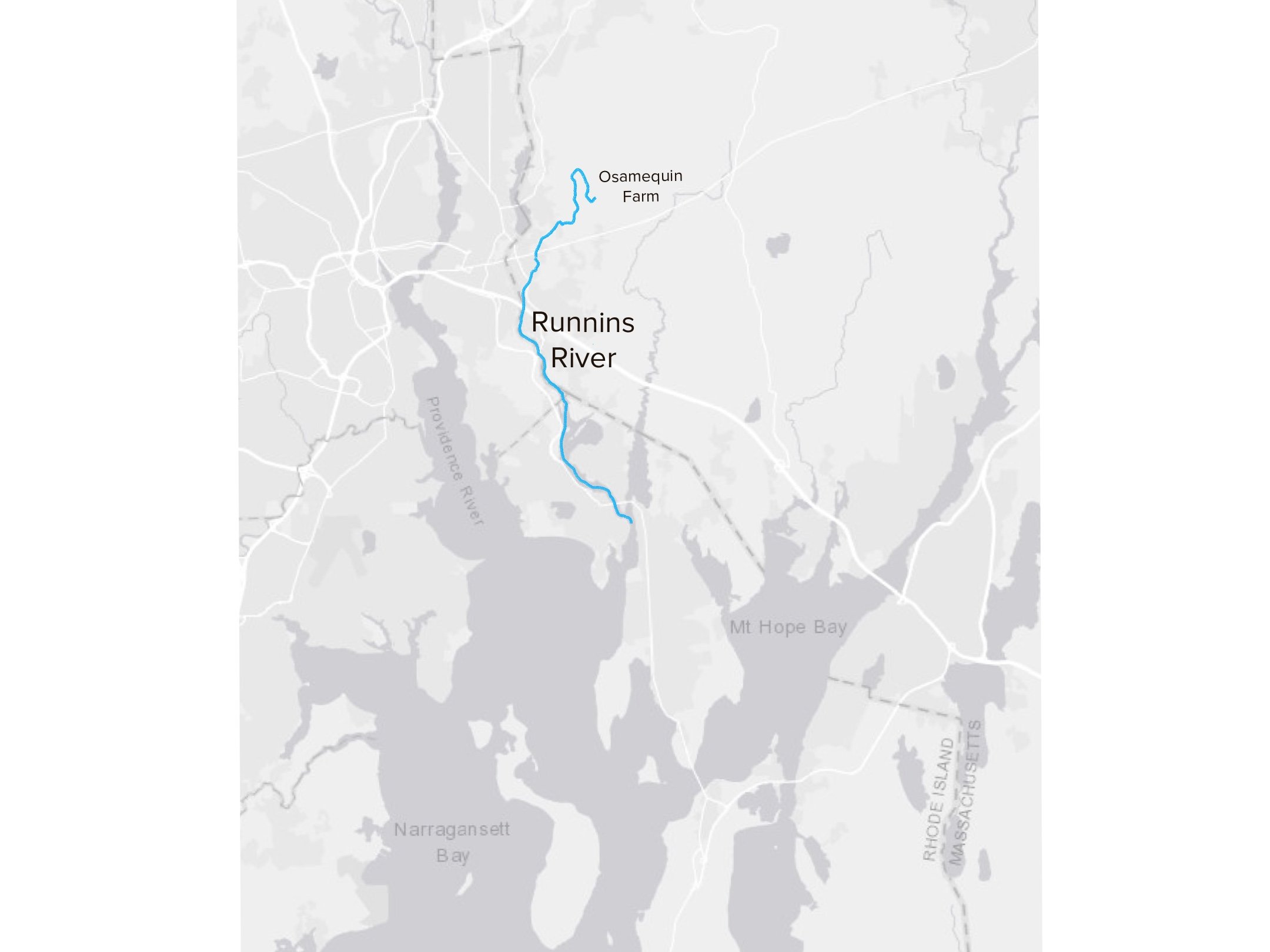

Multiple natural springs on the property feed this marsh. “The water bubbles up from there and then flows down into the marsh here and then to the other pond and then to this pond and then to the little pond right down there and then eventually into the into the meadow where it links up with the other one…” (Andrew) Eventually, these waters form the Runnins River.

Looking out over the marsh, you’re seeing the headwaters of a river whose waters nourish ecosystems all along its path… south towards the Hundred Acre Cove, then out to the Narragansett Bay. “This is valuable up here. This is so valuable to have the source, the gathering place, so intact.” (Don) That’s Don Doucette, from the Runnins River Watershed Alliance, which advocates for the protection and conservation of the Runnins River.

But the Runnins River doesn’t only connect us to the ocean and the life it supports–it also connects us to the past, and to the many people who have relied on it over time. It’s said that the First People of this land referred to this place as “dwelling at the long damn.” Andrew Jencks, one of the owners of the property today, says… “So the where the bridge is is the long dam. So essentially, that was a dam and what the Native Americans did, as my understand was, they would block off they would they would block the the water from going underneath while on the road or block the dam and … that would dry out the the swamp down here, or the marsh… So then they'd go in and they harvest all the marsh hay. And then they would open the dam back up and let the water flow back out into the marsh.” (Andrew)

The process of colonization disrupted these traditional Indigenous land management practices, as colonizers forced the Pokanoket from their ancestral land, often violently. The landscape was transformed as Indigenous ways of being with the land were replaced by colonial ones, often grounded in extraction. Look closely, and you can see the 100-foot-long stone dam that settlers constructed here in the 18th century. This dam, unlike those created by this land’s First People, was permanent, used to control the flow of water for field irrigation into the 20th century.

The Sagamore and Sachem of the Pokanoket tribe today couldn’t say exactly how their ancestors interacted with this marsh, or whether they built temporary dams here. They point out how this rupture in memory is another result of colonization: “We were kept off the land. So there are stories that were told, lots of stories got lost, some stories didn’t get told, when you’re not somewhere, it’s hard to tell a story when you’re not at that place.” (William)

But they also had new, joyful stories to tell about this place, from more recent generations… “My cousin, my cousin, Darlene. morning dove, you know, she said right over here, the pond down there. You know, how her her mother, her grandmother, her grandmother, I think, used to go swimming in that pond.” (Tracey) “Me, my cousin Harold, my cousin, oldest Weeden, we would take and Richard, we would come out here to Rehoboth. We used to ride on our bicycles to see his father. And this one, we should stop and swim in that pond. And one day I walked there to that water and I see these snakes all around, and I said, what's that? Well, there's snakes in this water? Well, I'm outta this water! (laughter).” (William) “But you know, at first, so long we were kind of kept off of our land. And, you know, and so it feels good to be able to tell our story and to be able to openly come on the land and talk about who we are.” (Tracey)

Now, these waters support the growth of crops throughout the farm and provide a home for all sorts of wildlife…including snakes. This one spot weaves together so many stories at play here at Osamequin Farm–the first peoples’ footprint on the land, the colonial era modifications, and the symbiotic relationship between the farmers and the native landscape.

That’s why you might recognize this image. The stone wall in front of the marsh, flanked by native plants like Goldenrod and Joe Pye weed, has become the logo for Osamequin Farm. Sarah, the farm director, explains, “We chose this as our logo because the marsh is really sort of the heart of the farm. We know that marshes and wetlands were important to the indigenous people of this area. And the that moment at the edge of the marsh sort of captures all of the trajectory of one piece of land for for many different communities. So we've got the marsh and then the stone wall which was added in colonial times. And then the paved road that you're standing on to look at the Marsh was added even later. And so our hope is that that image sort of captures all of the different eras that this farm has been through and the marsh has really endured and been a constant throughout that entire trajectory and into the future as well.” (Sarah)

With a little bit of attention, this place—like any place—has lots of stories to tell. On our next stop, we’ll hear about some of the families who have called this farm home for the past three hundred years.

-

-

In order of appearance:

Jordan Schmolka - narrator

Andrew Jencks - Osamequin Farm property owner, resident, and board chair

Don Doucette - member of the Runnins River Watershed Alliance

William (Winds of Thunder) Guy - Sagamore of the Pokanoket Tribe

Tracey (Dancing Star) Brown - Sachem of the Pokanoket Tribe

Sarah Newkirk - Farm Director, Osamequin Farm

-

Keep walking down Walnut Street until you see a house on the left (about 200 feet). Listen to the next stop, “Six Generations of Carpenters” from the driveway, looking out at the house—but please be mindful that the house is still a home/private residence!