Cooperative Farming at Osamequin

-

“My name is Sarah, and I am the farm Director here at Osamequin Farm.” (Sarah) Sarah’s been here since 2017, when she worked with the Jencks family to turn the farm into a nonprofit. “Andrew and Stephen, the Jencks brothers had been at different times living on the farm and maintaining the farm with their mother for a long time. And then, after she passed, they took on full responsibility. And I think it was at that point that they realized that this place was something that could possibly be better used if it was shared.” (Sarah) “Using the land to benefit the community to make it a community resource. There's no point in having this beautiful place if people aren't able to come and walk it and enjoy it and do all this kind of stuff.” (Andrew) “So we established Osamequin Farm, the nonprofit to really develop a structure around which we could share this space with the most people possible and have an impact. and bring as much life onto the farm as possible because the farm really thrives when it has life on it.” (Sarah)

Sarah met Andrew and Stephen Jencks in the summer of 2017. “And through a series of conversations, we decided that maybe the best use for the farm would be to turn it into not just a community space, but also a cooperative space. Because I had been a vegetable farmer on a small scale for about seven years at that point. And what I saw in the farm was potential to house lots of small farms.” (Sarah) Together, they developed a vision for Osamequin to house a cooperative of growers, called resident farmers.

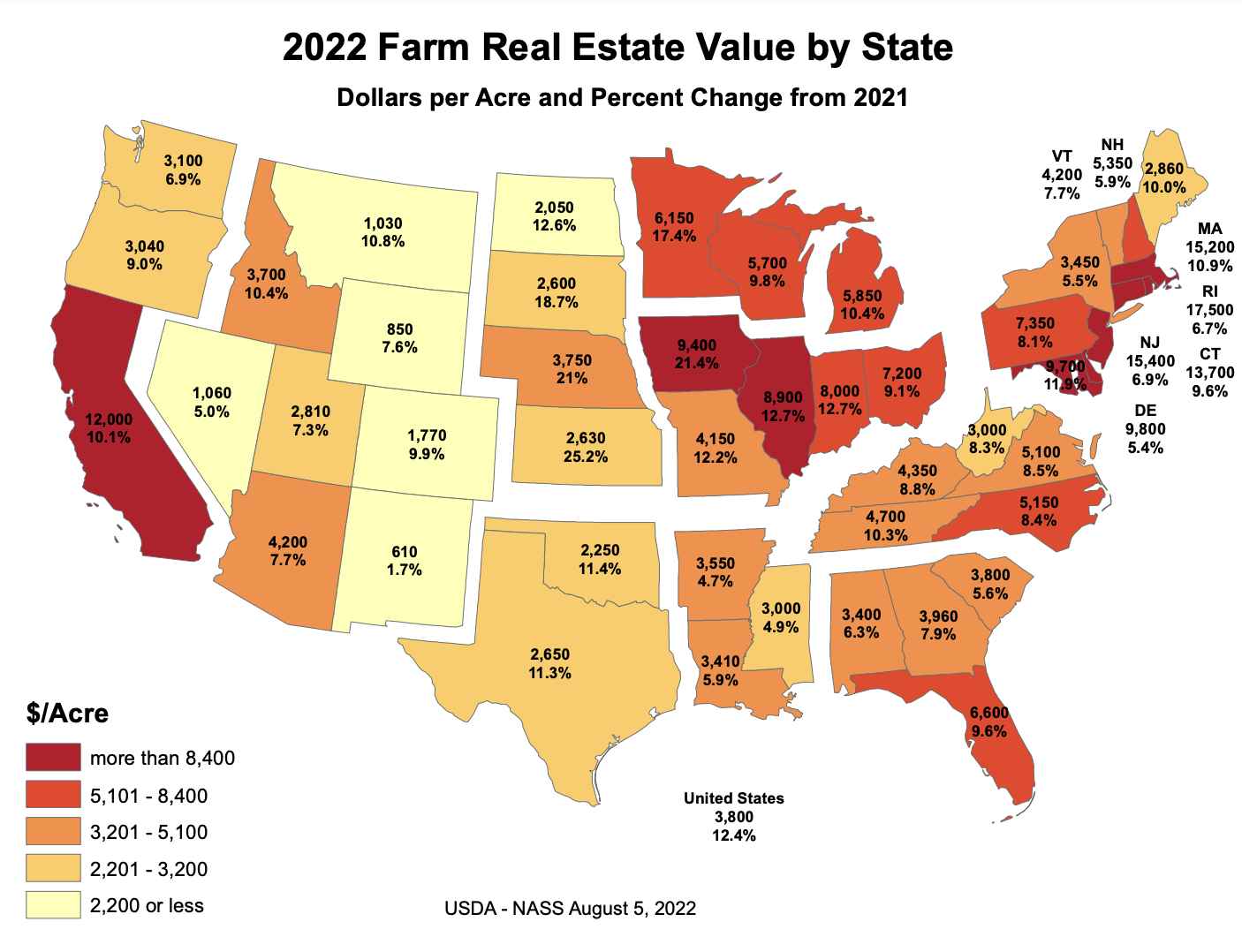

Land is the most basic, fundamental need for any farmer. Some farmers are born into agricultural families, and inherit land that has been passed down through generations. But those who don’t already have access to land have to find land to farm on their own—and that’s no easy task. Open land is scarce in this region, and Massachusetts and Rhode Island have some of the highest farmland real estate prices in the entire country. These realities only perpetuate inequities that are already deeply rooted in the industry: Today, white farmers manage 99.7% of all agricultural land in Massachusetts.

Because prices of available farmland often make it financially impossible to purchase land, young farmers, beginning farmers, and farmers of color often have to lease their land, which comes with its own challenges… “Being a non landowning farmer is scary because being a farmer is very, very challenging. And you're like pouring a huge amount of labor into something that ultimately enriches the soil if you're farming in the way that we are farming. And a lot of what you're doing is creating like a a bank of fertility and cyclical systems that are working with nature that cannot be picked up and moved anywhere. And not to mention, like, a lot of the infrastructure that makes a business possible is heavy infrastructure. It's not something you can actually put in a U haul. It's like got a foundation made of concrete, and so it stays where it is. So it can be scary to like invest in that stuff when you are not the owner of the land.” (Sophie)

“The idea behind the cooperative farming model was to really make it easier for small farmers, beginning farmers, farmers who are just getting their feet under them to have a thriving business and to figure out what they're doing without having all of the hurdles of building infrastructure and investing in some of the larger pieces of a farm that are tricky to invest in.” (Sarah)

“Folks are farming about one to two acres each and we provide them with water to their field, either from a well or from a groundwater source.” (Sarah) Resident farmers here also have the option to utilize shared marketing structures and infrastructure. This part of the farm is home to many of those shared resources. “We have a new greenhouse that we built last year in 2021 that everyone will use for their nursery propagation….And then we have a fleet of sorts of small tools and equipment that people can share like our gators, for moving things around the farm, mowers and weed whackers and hand tools and things like that. We also have a wash station that everyone shares for washing their produce, which has become sort of like the hub of folks getting together. And it's where you tend to run into the other farmers and catch up on what's happening in their fields and in their lives. So it's a great space for connection. And then we also have a shared refrigerated unit for storing produce until it's sold. So we call it the cool bot. And everyone has a space in there for their own stuff.” (Sarah)

“These are all things that are if this was just like a raw piece of land, it would be very, very difficult for any one single farmer to establish those things.” (Sophie) That’s Sophie Soloway, the founder of Hocus Pocus Farm, and one of the first resident farmers here at Osamequin. “The way that Osamequin was structuring tenancy and shared infrastructure was specifically aimed at benefiting small farmers and Sarah was a vegetable farmer at the time that it was all starting. That was her career. So she felt, I felt like she like intimately understood what a small farmer might need. I feel really hopeful that the infrastructure that’s here will make farming a realistic prospect and open the doors in a real way and like in a farming is actually a viable prospect kind of way to more farmers.” (Sophie)

John McGarry, who runs Muck and Mystery Farm, is also a resident farmer here. “I didn't grow up on a farm or gardening. And the infrastructure is a huge thing. I definitely like could not and was not conceiving of starting a farm as something I could do because the irrigation and the propagation and the wash area and storage all of that is just beyond the resources I could commit. I wouldn't be doing what I'm doing if there wasn't, like shared infrastructure support here.” (John)

And while the cooperative model can help support new farmers as they get their start, it can also provide space for folks who have been farming for generations to sustain those practices. “My name is Nhia Lee and my nationality is Hmong.” (Nhia) Nhia Lee and her family lease land here at Osamequin, where they grow many of the same crops their family once grew in Laos. “ Hmong people, usually back in Laos, they, they are the biggest farmers in Laos. They do like mountains and mountains of farm and that's their survival food that they they do every year, you know. So that's a major, major thing that they do in Laos, even nowadays they still do that, to find food for themselves. When we come to America, as a refugee, we don't want to lose that part of life. So we still wanted to bring that into our life, and living in America.” (Nhia)

In her plot, Nhia grows mostly lemongrass. “I use for cooking - so every time I cook I always use it or when I'm when I needed I saved some in the fridge. And lemongrass are good medicine. So they are very good medicine. Like even right now with COVID we use a lot a lemongrass for tea. We drink lemongrass. Lemongrass is good for, and it has a lot of benefit that you know you can use. So it's just not an herb, it’s a medicine that my people are using for a long time.” (Nhia)

The Lee family farm is an intergenerational project—Nhia’s mom, mother in law, and aunts have all grown food for their families here, too. “You see the old people that they still continue with a farming because they, they don't want to lose that they don't want to lose that kind of life, and they don't want to lose that kind of feeling that the you know, they don't feel like back home, you know, so that that's why they continue doing that. I'd like to share because, you know, a lot of people they don't know about, about us. A lot of people they don't know about Hmong people. They don't know where we came from or what we do or who are we.” (Nhia)

There’s no question that this place offers lots of resources. “So having them is an incredible gift and then the question is how to preserve them, work on them, fund them, use them equitably share them amongst ourselves and like really, like use them to their full potential.” (Sophie) “In our first year, we invited on five different resident farmers to be a part of the cooperative and we've retained most of them. We've had a little bit of turnover in the past few years. In the grand scheme of things, it's, it's still quite new. And so, you know, things are always evolving. We're always improving, and learning and adjusting. And that process will continue. Probably forever.” (Sarah)

[N6.14: At our next stop, you’ll hear about how land conservation here at Osamequin helps us protect the future of small scale farming in the area.]

-

Osamequin Farm resident farmers: Muck and Mystery Farm, Lee Family Farm, Hocus Pocus Farm, Night Garden, Granja Sin Fronteras, Co-conspirators wines

Young Farmer Network of Southeastern New England

2017 Census of Agriculture: Race/Ethnicity/Gender Profile, Massachusetts, USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service

-

In order of appearance:

Sarah Newkirk - Farm Director

Jordan Schmolka - narrator

Andrew Jencks - Osamequin Farm property owner, resident, and board chair

Sophie Soloway - former resident farmer (Hocus Pocus Farm), current board member

John McGarry - resident farmer (Muck and Mystery Farm)

Nhia Lee - resident farmer (Lee Family Farm)

-

Keep following Walnut Street as it heads into the woods, lined by the stone wall on your left side. Walk up this forest lane until you reach the “top” where you’ll find a fork in the trail. Pause at this fork and listen to track 7, Conserving the Land.