Establishing a Homestead

-

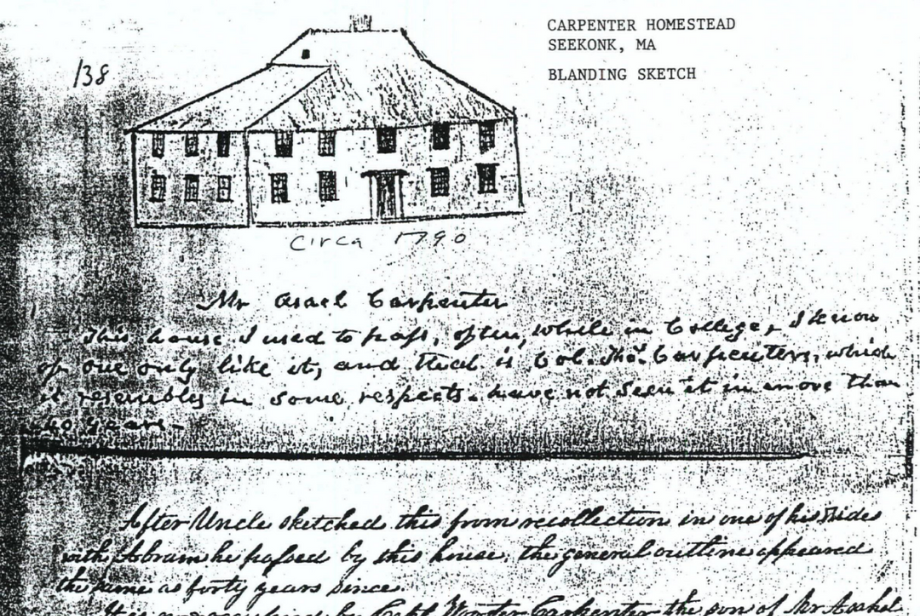

This house is one of the oldest existing houses in Seekonk. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Carpenter Homestead, the house was owned and inhabited by the Carpenter family for over 200 years, passed down through six generations from around 1720 to 1939. But how did they get here? Who were the Carpenters?

The Carpenters of Rehoboth and Seekonk are descended from William Carpenter, who was born in England in 1605. With his father, his wife, and their children, William boarded the ship the Bevis in 1638, setting sail for the colonies and landing in Weymouth, Massachusetts.

At the time, waves of new settlers from overseas were causing the English populations of Plymouth and Massachusetts Colonies to swell. More settlers required more land—and this put the Massasoit Osamequin under increasing pressure. In 1641, Osamequin sold 64 square miles of land to English colonists who envisioned a new settlement on the property, which included what is now Seekonk and Rehoboth.

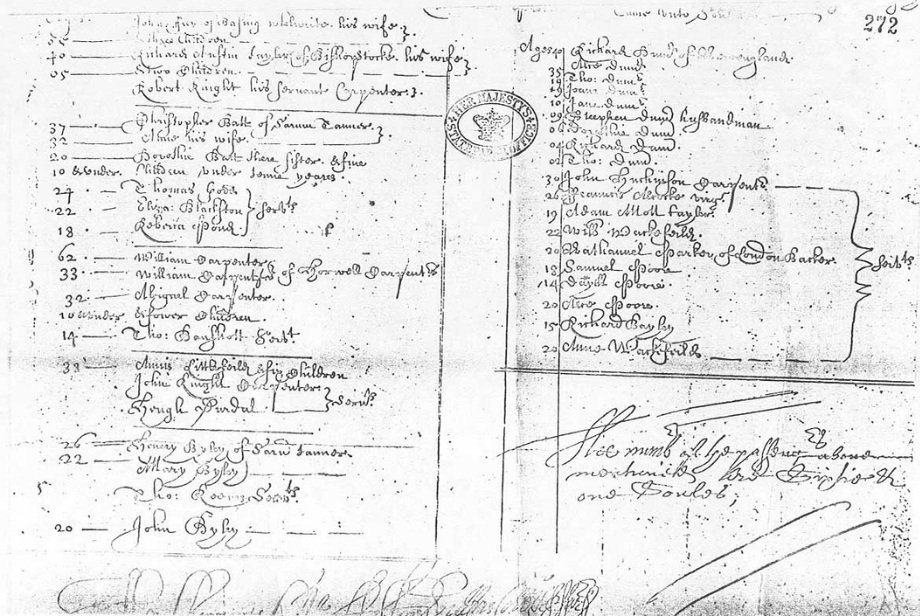

The Reverend Samuel Newman of Weymouth was told to round up potential settlers for this newly acquired land. William Carpenter seized the opportunity. In 1643, he joined with a group of 57 other Weymouth men to establish a new settlement, which the Reverend Newman named Rehoboth.

“And so they settled in the area of Rumford that is called the Ring of the Greens.” (Danielle) That’s Danielle DiGiacomo, director of the Rehoboth Antiquarian Society’s Carpenter Museum. One thing to note: the borders of Rehoboth, Seekonk, and surrounding towns…even the states of Rhode Island and Massachusetts!...have shifted a lot throughout this history. It gets confusing. “And then from that initial area,... people moved outward and claimed pieces of land and the old borders of Rehoboth.” (Danielle)

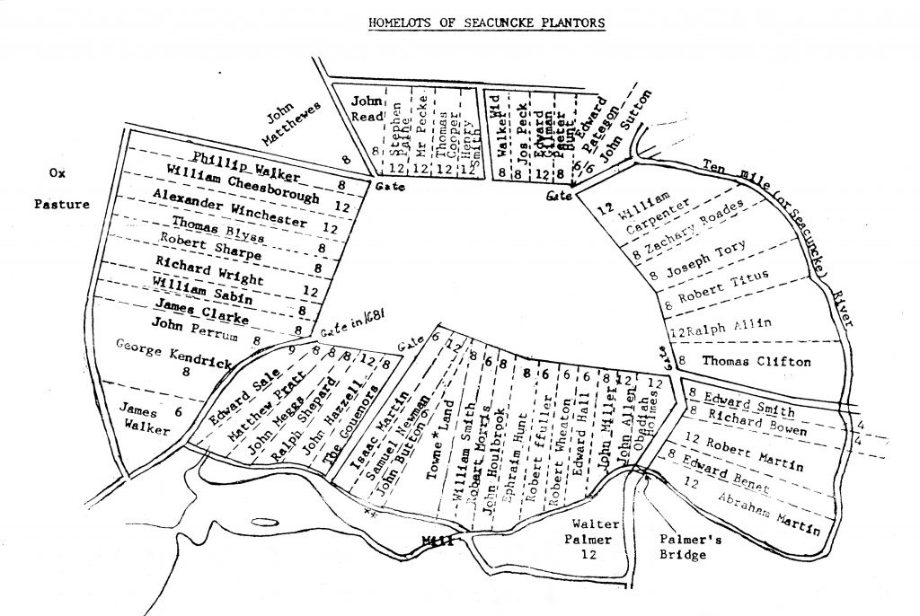

The 58 male settlers—sometimes called the Seekonk Planters—drew lots to decide who would get each property along the Ring of the Green. William Carpenter drew tenth. He became the town’s first proprietor’s clerk. His son William followed in his footsteps as the next clerk, then his son, Daniel…in fact, for the first 200 years of Rehoboth’s history, the town clerk position was almost continuously held by William Carpenter’s direct descendants.

The Ring of the Green was, in fact, a ring: the individual family lots were arranged in a circle around an enclosed central area for livestock. Also in this central area was the Newman Meeting House, used for church services and settlement business, and a cemetery. Scattered throughout the settlement were five garrison buildings for security.

The need for this militaristic infrastructure speaks to the continued context of violent conflict with the people Native to this land. Though the Massasoit Osamequin had sold the land in 1641, it’s essential to understand the conditions under which this sale had been made. English doctrines of land ownership were incompatible with Indigenous ways of being, which view the land as relative, rather than property. Like Indigenous leaders throughout the Americas, Osamequin was forced to operate within an imposed foreign legal and economic system under threat of violence. At first, even after losing official title to their lands, Native people sometimes retained customary rights of access to continue the practices that sustained their livelihoods and cultures. But over time, settlers increasingly began to enclose their property and defend it against any access at all by Native people, as they did at the Ring of the Green.

“So how do you how do you hunt, you know? They might as well have just said, well just lay lay down and die, cause how do you hunt and eat?” (Tracey) In 1676, Metacom (Osamequin’s son, also known as King Philip) and his warriors attacked and burned the Ring of the Green to the ground. This was in the midst of King Philip’s war, which saw the highest casualty rate of any war in American history. Thousands of Native people were executed, or sold into slavery. “It was so bad that after the kingdom war, the Barbados, they, they pass the laws and 1676 and they wouldn't accept any more captives of the King Phillips war. It changed the whole dynamics of our way of life life, because we had to go into hiding after that.” (William)

It’s likely that the Carpenters established their homestead here, on this land, in the aftermath of King Philip’s War. “So that the original house, my understanding is the original house, it was a half above half below ground, sort of sod roof structure that was put in was built in the 1680s. Although it's not really been confirmed.” (Andrew)

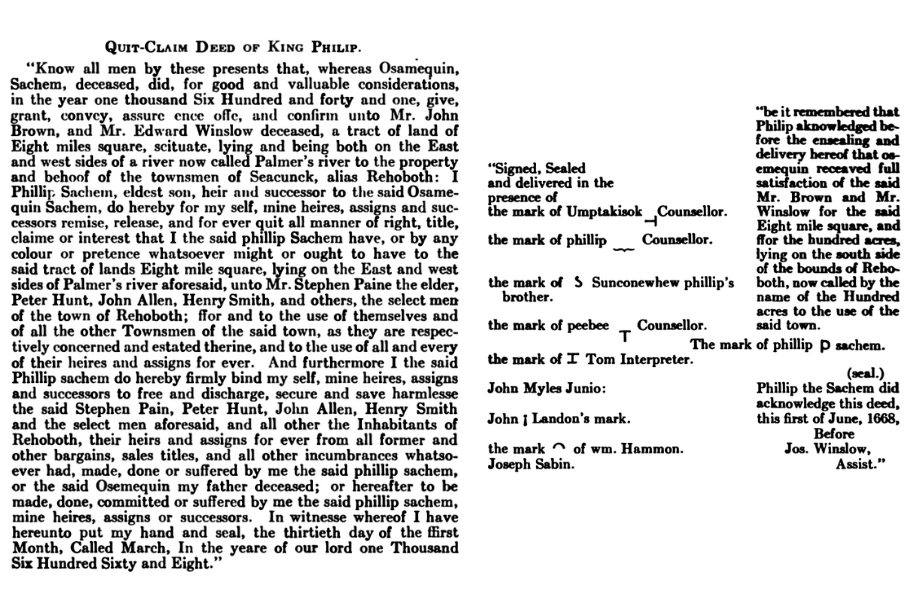

We do know, though, that in 1668, King Philip signed a quit-claim deed relinquishing his rights of access to all Pokanoket land sold by his father, Osamequin. This document was held by the Carpenter family, and remained here on this property for nearly 200 years before being donated to the John Carter Brown Library—a marker of the family’s entanglement with the history of Native land loss.

To learn about the family members who made their home here during those 200 years, listen to the next track: “Six Generations of Carpenters.”

-

-

In order of appearance:

Jordan Schmolka - narrator

Danielle DiGiacomo - Museum Director, Carpenter Museum

Tracey (Dancing Star) Brown - Sachem of the Pokanoket Tribe

William (Winds of Thunder) Guy - Sagamore of the Pokanoket Tribe

Andrew Jencks - Osamequin Farm property owner, resident, and board chair

-

Keep walking down Walnut Street and follow the left fork to head down to the barn. Take a seat at the picnic table or under the spruce tree while you listen to the next track, “From Carpenter to Jencks.”