In the Forest: Woods Ecology

-

As you walk through the forest, notice the trees around you: how long do you think they’ve been here? What do you think they’ve seen? “In terms of the lifespan of a forest or trees, it's baby, you know, baby forest.” (Dylan) That’s Dylan Block-Harley…earlier you heard from him about growing up in the neighborhood and walking around in these woods as a child. Now, Dylan is a professional arborist, and he’s contributed his tree care skills to help manage the woods on the property. “Experientially, like, what we call the woods or the forest is like, very young, you know, it's not, it's not old growth forest.” (Dylan)

There were once very old forests here, though. The First People of this land lived in close relationship with these forests and actively managed them to nourish woodland ecosystems that were rich in life and productive with food. For example, the practice of cultural burning—periodic, controlled fires—increased and maintained dense populations of berry bushes and selected for large, fire-tolerant, nut-producing trees. Fires removed leaf litter and smaller understory trees, promoting the growth of good forage for grazing animals on the forest floor. “We controlled the land differently, you know, we, we lived in harmony with the land, we didn't make the land live, to serve our needs, you know, we made sure you know that when we, you know, farmed, we didn't deplete the resources that we didn't farm, the same plot of land over and over and over again, like people do today, you know, we, you know, knew that we were using the land, but the generations after us would also have to use the land, so we wouldn't strip the land. Natural, you know, yeah, we were natural environmentalists. So we would use the land knowing that the next seven generations had to do the land.” (Tracey)

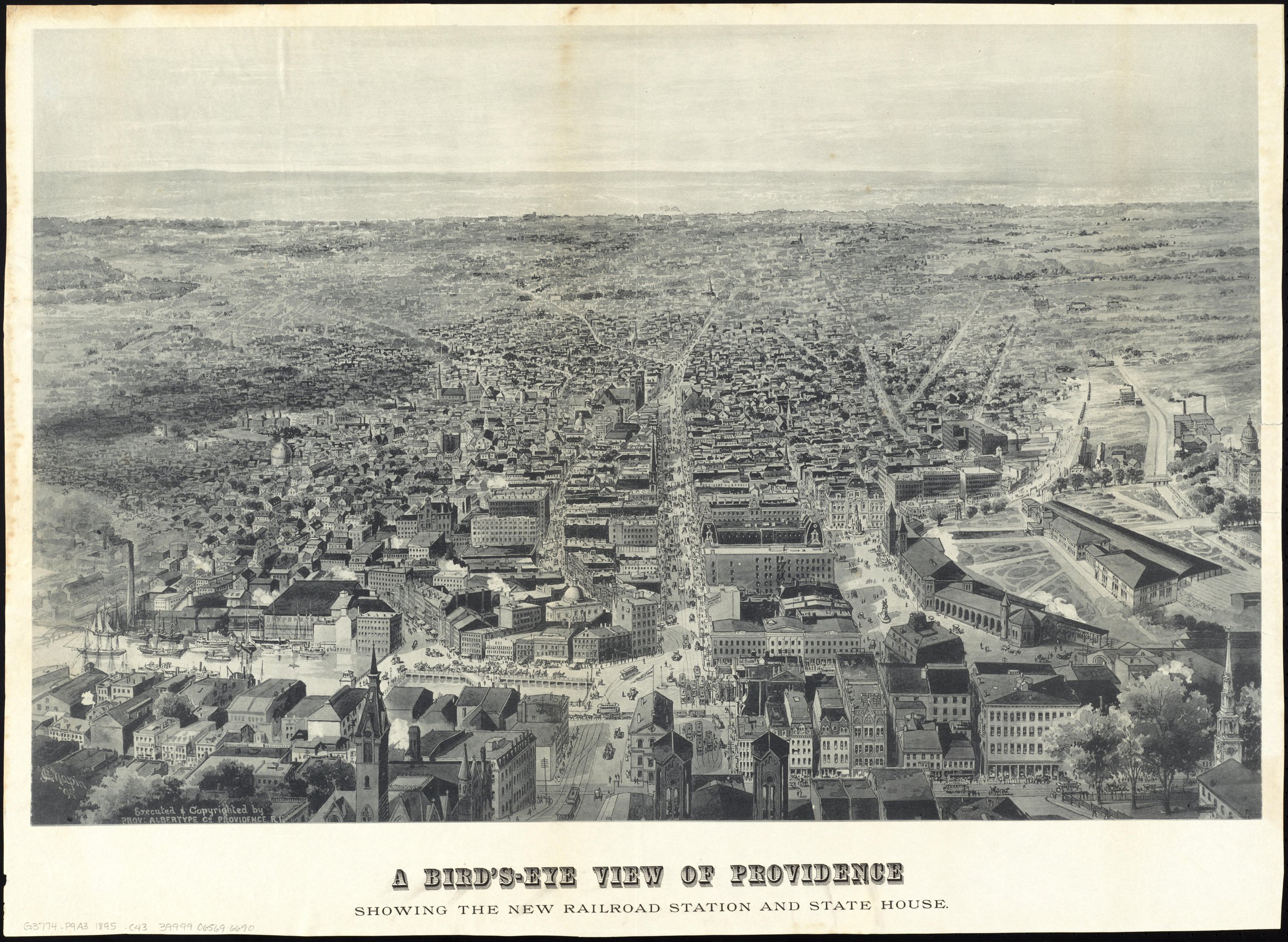

But throughout New England, English colonization brought deforestation. In the two centuries following the arrival of English settlers, 80% of New England’s ancient forests were cleared for pasture, tillage, orchards, and buildings. “I have pictures back to the 1900s that were taken must have been taken from a balloon or something. Or maybe an early plane, I don't know. But basically from it was a shot from Providence towards Plymouth. And it was apparently not a tree in sight. I mean, they cut everything down. And that was you know, so it was, you know, while it seems very wooded and kind of, you know, old growth is not it's you know, there are few trees except for around houses that have been around for for more than 150 years.” (Andrew)

By the early twentieth century, the local economy had shifted from agriculture to industry. Later generations of the Carpenter family began to abandon many of their pasture fields—and the forest began to re-grow. But the forest that arose looked very different from the one that had existed pre-colonization. “One of the most important things is when people sit and walk the land, they say, Oh, these are how the indigenous people like, this is what they saw. No, a lot of the plants are invasive species. A lot of you know, the trees and what's grown here wasn't here. We didn't have walls to contain farm lands. A lot of the way the land is evolved is because you you have the cattle, the sheep, we didn't have those animals here, we didn't have cows here.” (Tracey) The new forest was shaped by what the land had experienced, including intense pressure from grazing livestock and the disruption of traditional Indigenous land management practices. “We used to do controlled burns, and, you know, the control of ours, you know, the, the wildlife, you know, these are things that we can't do, they don't, they won't let you burn.” (William) “So what you see today isn’t what you would have saw back then.” (Tracey)

This forest tells a story, if you know how to listen. “There's a history that you can actually see okay, based on these lands, based on the landscape based on these features, this was cleared to us as pasture at one point and now the forest has going back…What is what is growing? What is dying out? what is taking its place?” (Emily Leeser) That’s Emily Leeser, who’s worked here for several years. Walking through these woods, she pays close attention to the stone walls that criss-cross the landscape. “Okay, right here, there's a pile of rocks. And that means that some at some point, this land was cleared, probably for pasture for sheep, or other animals. And they needed somewhere to pile up the rocks. And this is where they piled it. And like, this rock pile indicates that at one time this land was cleared.” (Emily Leeser)

Emily Shapiro, who also works on the farm and lives on the property, notes that these centuries-old stone walls often still mark boundaries of sorts. “I love the stone walls. Yeah. Um, it's so cool to walk around the woods and see the stone walls and then kind of notice the landscape on one side versus the other side. And to sort of think through whether that wall was there because it was a property barrier, or because it was, you know, separating pasture land from Woods, or whatever it might be. But sometimes you can see really like big distinctions just from one side to another.” (Emily Shapiro)

More recent histories have left their mark on this forest, too: like climate change, and the introduction of invasive species to this land by globalized trade systems. “There was a back to back or like a sandwich of pest pressure and drought and then pest pressure again that just defoliated the trees, and they just couldn't recover.” (Dylan) Winter moths and spongy moths were both introduced to this region from Europe, with devastating consequences for native trees. “And so there's all these I mean, what were mature and like big oak trees, out in the woods that are just standing dead.” (Dylan)

“But a lot of mushrooms like to grow around dead oak trees…” (Emily Shapiro) And this gets at an important theme: disruption doesn’t always mean devastation. Life finds ways to grow in the midst of disruption, and sometimes, it flourishes. In many places on this property, the disruptions caused by changes in land use by humans have actually made way for new, interesting, diverse ecologies that wouldn’t otherwise exist here.

Garrett Crosby has spent many hours foraging for mushrooms at Osamequin Farm. “On the main kind of core farm, part of their property that's in use most frequently, there are a lot of species of trees that thrive here that aren't necessarily native like Norway spruce, and that I think, really changes things up from most of the foraging places I find around here because there are a lot of like, species that might grow in Maine, that we normally wouldn't get down here, but since there's Norway Spruce here, we do see them. Something really neat that I find here every year is Amanita phalloides, which is the death cap. And that's the most lethal mushroom in the world. And it's quite uncommon here….I think they think it was transplanted. When a tree is moved, and transplanted from maybe like Northern California or something to the East Coast, it's riding on the roots of those trees. And so I think because they have those Norway spruce and some other trees that might not be native here. I think the death catch probably hitched a ride on that, which that’s really cool.” (Garrett)

Now listen—almost any time of year, you’re likely to hear the sounds of birds here. “I think there's probably like 30 species, at least, if not, like, maybe up to 50 That would be there year round, just would always be there. There's probably like 50 or more that would breed there. And then probably, if you like, set up shop, and like decided to like, survey birds every day during migration, like April and May, you probably can get to like 150, maybe 200 species if, if you were like, really able to find everything, so it's a lot of stuff.” (Greg) That’s Greg Nemes, a naturalist who has led bird walks here at Osamequin. He points out that some of the habitat types that support this diversity of bird life actually wouldn’t exist without human intervention. “I just think it's cool that it provides a good amount of habitat, there's deciduous forests, there's coniferous forests, there's grassland. You know, there's human made structures which, like provide habitat for a bunch of different birds. And then even the livestock are also you know, they'll attract birds too. So there's just like there's a lot of richness to what could you know, be possible for birds?” (Greg)

Or take another example, deeper in the woods here: “The power lines, they cut through some time, I think in the 50s. And those have been an interesting element. They're, you know, they're sort of an eyesore, but there's a lot of interesting ecology below them. So for years, they sprayed them with Roundup from the air to kill everything in there. But the one thing that loved them was huckleberries and blackberries. So there's tons of Huckleberry wild Huckleberry and blackberry bushes, all up and down the power lines.” (Andrew) And who enjoys these berries? Lots of animals—including black bears, whose berry-filled scat can sometimes be seen on these trails.

“One thing about this place, I guess is that I feel as if I've seen just walking in the woods, and walking just anywhere around this property. I've seen plants that I've never seen just growing in the wild before…” (Beth) That’s Beth Brandon, an ecological horticulturist and landscape designer who’s done work here on the farm. Other people who spend time in these woods often echo that feeling: that they see things here that they don’t often see elsewhere. “I've had like a lot of firsts on this property, because it just sort of, it's so sprawling and large, and it's kind of so rich with. I feel like it's rich with history, but also like, it seems like all the critters really love it too.” (Isabel) “There's enough land that a lot of it is just allowed to be it's not being messed with all the time…. It's just, they're doing what it does. And there's just not enough places like that.” (Beth)

When you emerge from the woods and arrive at our second-to-last stop, you’ll hear more about how we emulate and encourage those natural processes through gardening and farming practices here.

-

-

In order of appearance:

Jordan Schmolka - narrator

Dylan Block-Harley - childhood resident of neighborhood, arborist

Tracey (Dancing Star) Brown - Sachem of Pokanoket Tribe

Andrew Jencks - Osamequin Farm property owner, resident, and board chair

William (Winds of Thunder) Guy - Sagamore of Pokanoket Tribe

Emily Leeser - Osamequin Farm resident and food plot manager

Emily Shapiro - Osamequin Farm resident and flower hill manager, resident farmer (Night Garden)

Garrett Crosby - forager, naturalist

Greg Nemes - naturalist, tour leader

Beth Brandon - ecological horticulturist and landscape designer

Isabel Watson - Osamequin Farm events, programming, and field support

-

Continue on the trail until you find yourself at the top of a field, looking down towards where you began your visit. (This walk will take about 8 minutes without stopping.) You should see a large sole evergreen tree, and a field that’s cropped in rows, bounded by a three strand electric fence (careful not to touch the fence, it may be turned on!)

Listen to track 9 as you make your way from the top of the field down to the other end.