Six Generations of Carpenters

-

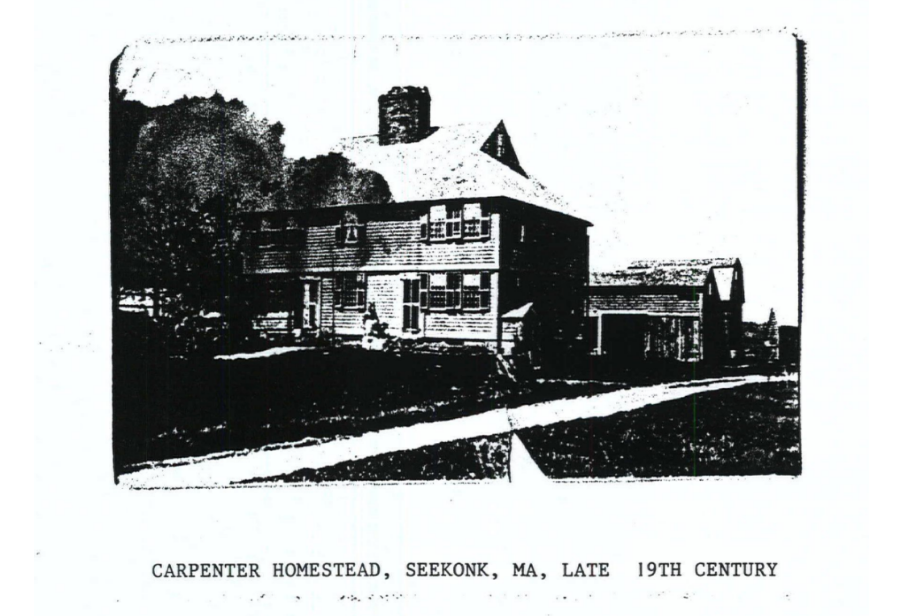

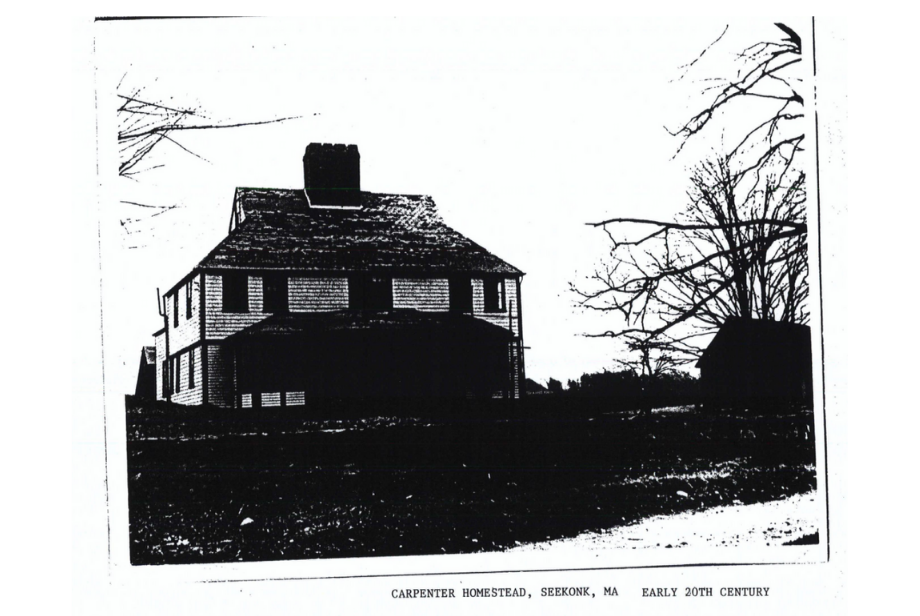

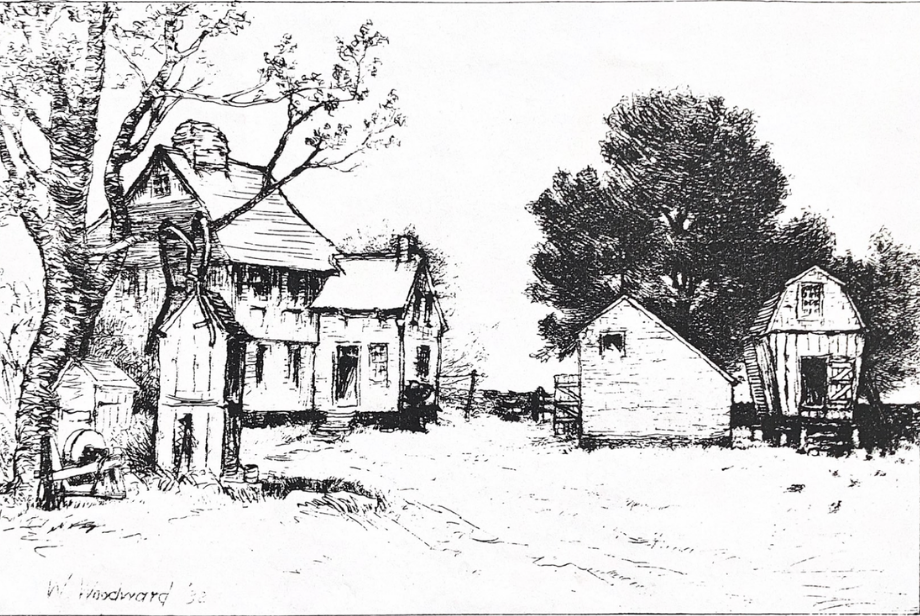

The house that stands now at 80 Walnut Street is thought to have been constructed in 1720 by Daniel Carpenter, the great-grandson of William, who came on the Bevis. That same year, Daniel married his wife, Susannah. Here at their homestead, they established a farm, most likely primarily for family consumption…Daniel and Susannah had 10 kids, and a lot of mouths to feed. The center section of the barn was built around this time.

“So Rehoboth always being a farming community was a very poor farming community like this is one of the better parcels of land that was in older Rehoboth. It's very rocky the soils not very good in all of Rehoboth and so there weren't a lot of large farms that could could sustain an entire family. It was smaller farms where the families ate most of the crops that they raised, and they all had to have other professions. And so they, they would hunt game and sell it in Providence or Boston. They would make things like buckles or buttons or the like fibers for weaving. So the carpenter family that lived it here seems rather well off compared to their neighbors in Rehoboth.” (Danielle)

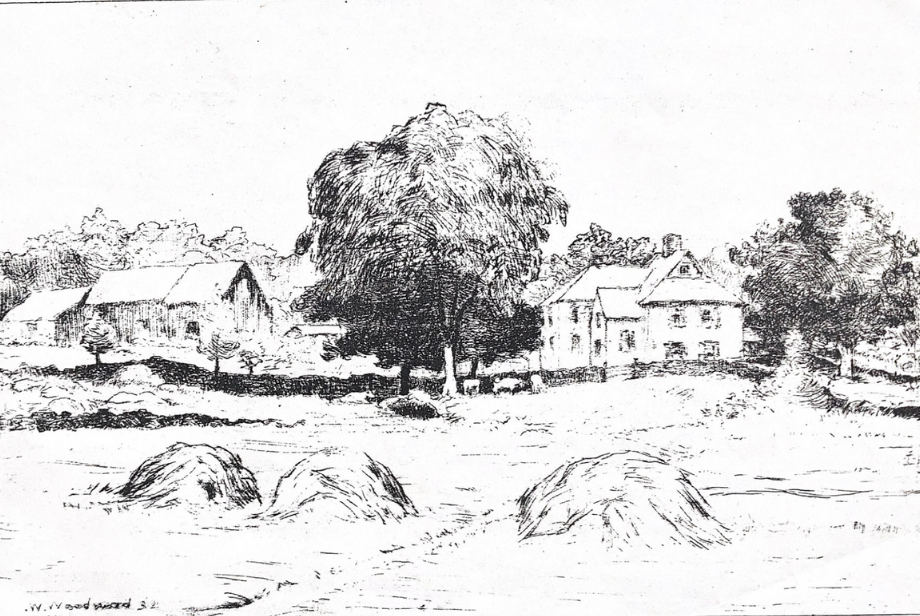

When Daniel and his family set up their homestead here, they began a period of more than 200 years of continuous farming by one family. Over that time, the Carpenters’ agricultural activities were probably fairly consistent. Farm production was varied…they grew fruit in the orchard west of the house and vegetables in gardens near the house. In the surrounding fields, they grew flint corn—which Native people had taught colonists to cultivate—and hay. They kept oxen and horses for transportation, hauling, tilling, and harvesting; sheep provided wool for clothing and mutton to eat; and cows and cattle provided milk and beef. They clear-cut almost all of the forests on their land for cultivation or grazing, maintaining only a small amount of woodlands to provide firewood for heating and cooking—and a few sugar maples for syrup.

These activities completely transformed the ecology of the landscape. Of course, there were the obvious changes—like the destruction of forest habitat, and the disruption of natural stream flow patterns. There were also subtler changes…and you can still see many of them at play in the landscape today, if you know where to look.

When lots of large grazing animals like sheep, cows, or horses are introduced to a pasture, plants that can avoid their grasp have a competitive edge. One way to do that is to grow in the form of what’s called a “basal rosette”--when all of a plant’s leaves lie flat on the ground, radiating in a circle from the top of the root system. This includes many of the plant species that are most common in pastures, old fields, and lawns here today—dandelions, plantain, common yarrow, sheep sorrel, curly dock…And most of these plants are not even native here! They evolved in European grazing ecosystems—and when those ecosystems were transplanted to New England, so were the basal rosettes.

Or let’s take another side-effect of having livestock around…poop! “Livestock will bring insects to feed on their waste. And that will bring birds and other insects, on to bigger insects. So like, I've seen a lot of praying mantises on the farm. And they, you know, are predatory on insects. They're predatory on anything they can get their hands on. But insects are their you know, their bread and butter. So, you know, if there's livestock and they're producing waste, there's smaller insects, mantises, and maybe dragonflies and stuff are eating those and birds are eating those.” (Greg) That’s Greg Nemes, a naturalist who has led nature walks here at the farm.

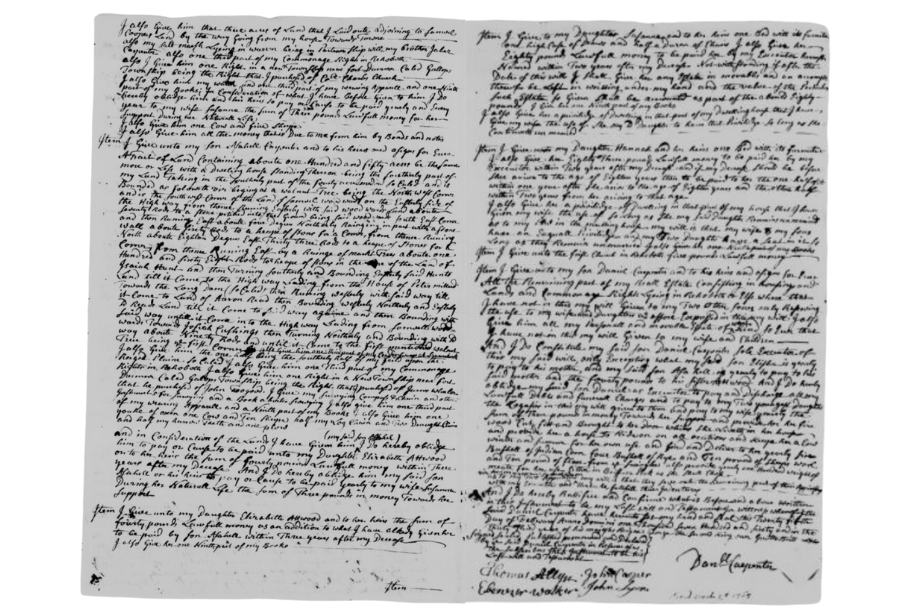

But let’s get back to the Carpenters… Daniel Carpenter died in 1763 and left his homestead—including the house, the barn, and 150 acres of land—to his son Asahel, who then lived and farmed here with his wife Molly and their 13 kids. Asahel probably built the eighteenth-century corn crib that still stands on the farm today (the greenhouse was attached later, in 1940). Asahel also commissioned an elaborate musical grandfather clock, which remained in the house here for over 100 years before ending up at the Carpenter Museum.

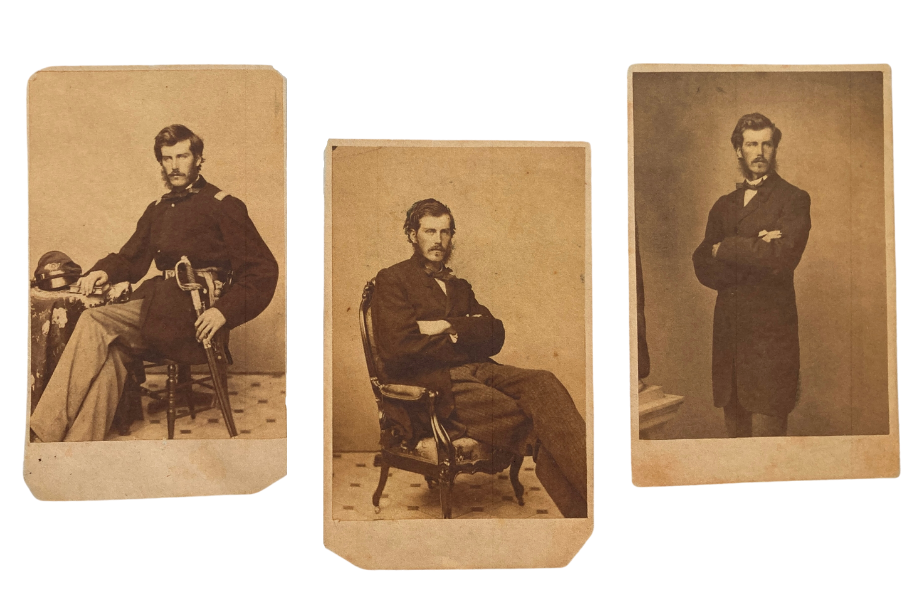

Asahel’s son Wooster then inherited the farm upon Asahel’s death in 1809. Wooster and his wife, Lovina, raised 11 kids here, including a son named George, who served and died in the Civil War. When Wooster died in 1858, he passed the farm to his son Horatio. Horatio then passed the farm to his son, Horatio Miles, who passed it to his son, George Carpenter, around 1930.

By that time, the local economy had transformed. While Seekonk was primarily agricultural into the 20th century, electric trolley lines, and then cars, prompted a shift towards suburbanization. George Carpenter was primarily a real estate and insurance agent, who operated the family farm as a gentleman farmer, with support from other family members living nearby. By this time, farming wasn’t a necessity for the Carpenters—just a part of family tradition and a tie to the past. George’s nephew Francis remembers that George mostly grew hay, most of which was sold to Rumford Chemical Works in East Providence for its horses—again, a sign of the changing local economy. George also sold hay to local fruit and vegetable truck farmers for use as mulch, especially for strawberries, a specialty of the expanding Portuguese population in the area. George and his wife Grace had no children, bringing the tradition of multiple generations of Carpenter families on this land to a close.

Move on to the next stop to hear about who came next.

-

-

In order of appearance:

Jordan Schmolka - narrator

Danielle DiGiacomo - Museum Director, Carpenter Museum

Greg Nemes - naturalist

-

Stops 4 and 5 are both around the barnyard - explore the exterior of the barn as you listen, say hello to our animals if they're nearby, enjoy the scent of the apple blossoms in spring and check the trees along the driveway for fruit in the summer: peaches, apples, and quince! You're likely to encounter residents and staff working on various projects around the barn, say hello and ask them what they're up to!